When Margaret Carreiro confesses that she is on the stump, she isn’t making a biologist’s pun. The ecologist is passionate about gardens and willing to take her enthusiasm from lecturing in a classroom to researching in the field to speaking to community organizations about the benefits of nature, and how we can incorporate a little bit of green into our everyday lives.

Lately the biology professor has been talking about biophilia, or humans’ innate push to seek connections with nature. The concept has spurred cities to look at becoming more livable through nature and to acknowledge that people grow happier and healthier with

more exposure to nature.

Carreiro and her colleagues are bringing biophilia to Louisvillians by helping to grow gardens in the middle of the city, creating urban homes for bees and butterflies to increase pollination and working with local parks organizations and greenhouses to save native plants in the region.

“I wanted something that was more positive and involving people,”

she said. “We don’t have to wait around for government to do conservation. We can do it ourselves.”

Carreiro’s efforts help ease her worries about the possibility of a world of children with what she termed nature-deficit disorder.

“There are a lot of kids that are not going to make it to a park on a regular basis,” she said.

But growing a little patch of garden wherever they are can help.

“Kids get exposed to a little bit of nature in their world and they find wonder in it. I think that’s healthy.”

And that goes for “college kids” too.

Not-so-secret garden

Students and others who stroll Belknap Campus notice an oasis of native plants and colorful insects on the west side of the Life Sciences Building. The Harriet Korfhage Native Plant Garden, named for a 1950 and 1963 UofL alumna and longtime Valley High School biology teacher whose family helped fund the project, is intended to support the education and research of UofL students as well as to educate others about indigenous plants. And for pollinators that alight, “it is a gas station and, I hope, a nursery,” Carreiro added.

The garden project was begun in 2015 by Ron Fell, biology department chair, and Carreiro with the collaboration of UofL’s horticultural groundskeepers under the direction of their superintendent, Greg Schetler. The crew transformed the lawnlike spot into a garden

with paths, underground water system, fence and soil enriched with compost from the university’s compost recycling site.

So far the garden supports about 70 species, and the department’s website lists its plants and information along with tips for starting small, pollinator gardens elsewhere. Biology colleagues David Schultz and Sarah Emery helped Carreiro decide on which plants, which were added in collaboration with area businesses Dropseed Native Plant Nursery and Plant Kingdom.

The plantings are intended as food and havens for pollinators, such as bees and butterflies, that have been threatened by environmental change. To keep the populations going, the plants need to include hosts that provide the caterpillars’ food. For instance, that’s why the garden includes milkweed varieties that can serve as a place for monarch butterflies to lay eggs and a food source for the resulting caterpillars. UofL biologists hope the garden

will become a way station for the migrating monarchs.

“Kentucky is really important on the flyback,” Carreiro said.

Native plants tend to offer the best nectar for native insects — the “gas station” function that she mentioned. And if the insects lay eggs, the plot becomes a nursery.

“Most people see this and see a garden. I see a conservation place,” Carreiro said.

Carreiro and Fell hope the on-campus garden will educate urban students who likely are unfamiliar with flora that is native to Kentucky and with the seasonal changes they can observe happening as they walk by and through.

Pollination stations

The garden also serves as a living laboratory for students, several of whom volunteer with faculty members to weed it. Perri Eason, director of graduate studies for the department,

was unable to walk through it recently without dropping to pull some unwelcome

foliage creeping into the path.

In one section rise some soapy, water-filled collection bowls on posts. From those, researchers gather insects to see what types of winged visitors frequent the garden. Similar bowls have sprouted all across the city as part of research projects examining

insect pollinators and how they vary from urban to suburban locales. The biology teams partner with the nonprofit Louisville Nature Center and area schools to select the spots.

Some bowls are perched in private gardens and in parks. Some research focuses on caterpillar production rates across the urban-suburban spread in an effort to see whether different garden habitats help them flourish or become a “death trap” by attracting

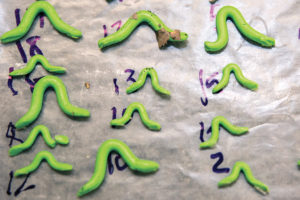

insects to their enemies. So those gardens get “planted” with bright green faux caterpillars molded out of soft, claylike Plasticine. Those caterpillars are glued to leaves on plants across the garden sites — 40 in each one.

“That’s a lot of caterpillars,” Eason said, smiling.

Eason and her students gather the faux caterpillars back up to a campus lab to examine closely for markings, a beak imprint or claw mark, for example, to help identify the predators that may lurk in gardens for the plastic bugs’ real-life counterparts. So far the predator rate is about the same from inner-city gardens to parks, from large areas to small spots, and from older gardens to newer spaces.

Along with saving pollinators, part of Carreiro’s studies includes the conservation of plants native to Kentucky and the region. Carreiro and students have worked for years with the Louisville Olmsted Parks Conservancy, particularly in a Cherokee Park project to gauge the impact of removing invasive, exotic plants such as honeysuckle that can suffocate native plants in woodlands. She also is testing an organic herbicide to see if it can work on invasive vine control but reduce the adverse effects on soil and organisms that harsher chemicals sometimes leave.

Growing the message

The biologists’ interests on campus and throughout the city have attracted devoted undergraduate and graduate students not just from their department but from other majors. Some, Carreiro said, are surprised to link urban nature to human health benefits. That’s part of her citizen-scientist mission: to get the word out in the community about incorporating native nature into daily surroundings.

“I’m happy to spread the word,” she said, “It’s a way to find common ground and get us to know each other.

“It isn’t just for nature — it’s for us.”